by Andrew Higgins

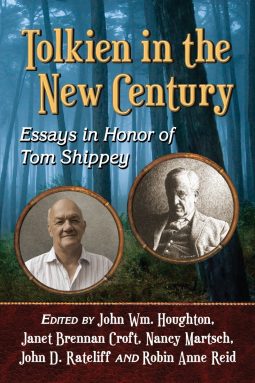

Tolkien in the New Century: Essays in Honor of Tom Shippey. Edited by John Wm. Houghton, et al. McFarland. June 24, 2014.

Eglerio! Tolkien lovers and explorers have rejoiced this summer with a group of books that I am sure have been on countless Kindles and read on beaches and by many pools. The joyous reading list started this May with the publishing of Tolkien’s own translation of Beowulf edited by Christopher Tolkien. It continued with several books including the mathom filled A Companion to J.R.R. Tolkien by Wiley Blackwell, edited by Stuart D Lee. Finally in late July we, like Hobbits on other Hobbit’s birthdays, were gifted with Tolkien in theNew Century: Essays in Honor of Tom Shippey.

It seems inevitable that great scholars eventually have festschrifts written about them. By definition a festschrift is a book honoring a special person, usually an academic, and presented to them in his or her own lifetime. (Tolkien was presented with his own in 1962.) The essays in this volume—apparently not called a festschrift because they do not sell widely under that name anymore—celebrates the work of one of the most influential scholars of Tolkien. Professor Thomas Alan Shippey’s thoughts and explorations on Tolkien, just one strand of his own voluminous body of scholarship, have shaped the very foundation for the explorative work of Tolkien in the New Century.

At the start of this volume, author John R. Holmes signifies the importance of Shippey’s contribution to Tolkien Studies by, in a very Tolkienian fashion, inventing the Anglo-Saxon word Scippigræd to refer to “those scholars, academics and Tolkien lovers who have been counselled by Tom Shippey.” As I read this, I reflected on my own Scippigræd moments with the great man himself at conferences and especially through the classes I have taken at Signum University/Mythgard Institute, including last year’s revelatory Philology through Tolkien course—and we wait in hope for Shippey’s teaching of more Mythgard Institute classes. (Beowulf anyone?) In the same introductory chapter, Holmes also offers a slightly ludic, but very informative, ten-point plan for how to be like Tom Shippey, with the last point being “never listen to advice.”

The volume itself is is split into several sections In “Memoirs” there are several brief and interesting remembrances by members of the Scippigræd, including musings on the popular game of being the first to spot Tom Shippey at the Kalamazoo Medieval Congress conference, and Tom’s incredible work and involvement with the U.K. Tolkien Society going back to 1977. Tom was “discovered” by the then–Secretary of the Society Jessica Yates through several of his Old and Middle English book reviews in The Times Literary Supplement, which mentioned Tolkien, and from the Tolkien questions Tom had set in the Mastermind Quiz Book.

In the second part, “Answering Questions,” several Tolkien scholars respond directly to questions and issues that Shippey has raised in his encouragement of further academic exploration of Tolkien’s work. Included in this section is a paper by the other foundational scholar of Tolkien Studies, Dr. Verlyn Flieger, whose “The Jewels, the Stone, The Ring, and the Making of Meaning” masterfully builds upon a question Shippey raised once: “What did Tolkien Mean the Silmarils to Mean?” In Flieger’s tour de force exploration, she not only answers Shippey’s question but also shows how Tolkien developed his ability to “corral his material and harness it to his design.” Another standout paper in this section is Nancy Martsch’s “The Lady with the Simple Gown and White Arms,” which takes up another one of Shippey’s suggestions for scholarship around early influences on Tolkien and explores both the texts that influenced young Tolkien and the original book illustrations by such Victorian artists as Lancelot Speed that were included in editions of Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books and H. Rider Haggard’s Eric Brighteyes.

Part three, “Philological Inquiries,” contain three excellent papers on the role and use of philology in Tolkien. Of the three papers, I thought B.S.W. Barootes “‘He chanted a song of wizardry’: Words with Power in Middle-Earth” made a very compelling argument for analysing the pattern of decline in the creative and sub-creative powers of language in the chronology of Tolkien’s world. Barootes achieves this by using as a critical framework the theories of Giambattista Vico and Northrop Frye to contextualize the decline of the power of words in the chronology of Arda. I heard an early version of this paper at the U.K. Tolkien Society Return of the Ring Conference, and Barootes has developed his early ideas masterfully—much to explore here.

“The True Tradition” turns to a particular focus of Shippey’s on considering Tolkien’s interactions with medieval antecedents. Again, it is hard to pick favourites, but the one I have the most underlines and notes for is John D. Rateliff’s “Inside Literature: Tolkien’s Explorations of Medieval Genres.” In this paper Rateliff critically analyses several Medieval sources Tolkien would have known to convincingly show how Tolkien uses the insights he gained from medieval sources to reproduce the appeal of medieval literature in his own modern works. Rateliff’s expansive and explorative study show that Tolkien’s work is so suffused with medieval borrowings that today Tolkien’s creative work serves for many as a portal into reading and studying Medieval literature. The paper is also interesting for Rateliff’s under-analysed samples of Tolkien’s work he brings into his study including “The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun,” “Iumbo,” and “Fastitocalon.”

In the last section, “Perspectives from Outside The Cycle,” Richard C. West provides a counterpart to his landmark paper “Turin’s Ofermod” in Tolkien’s Legendarium: Essays on The History of Middle Earth (2000). West returns to the Turin Turambar cycle to show that Tolkien’s constructed secondary characters in these stories to examine musings on the virtues and flaws of the heroic ethos that informs so much myth and literature. In this paper West looks at the characters of Gwindor son of Guilin, Beleg, Dorlas, Hunthor, and Turin’s sister Nienor to show that they to by their association with Turin are ensnared in the same curse that Morgoth speaks to Hurin.

For this brief review of a critically rich book I have just highlighted a couple of the joyous explorations that this volume provides. I would highly recommend this book to all lovers of Tolkien, philology and fantasy literature. I can always judge a book by the number of underlines (in this case on the Kindle) and notes I have made after a first reading. This volume has many for thought, exploration and follow-up.

In a sense, when I finished the first (of many) reads of this book I felt the way I have done after being in the presence of the great man this volume honours, Professor T. A. Shippey—excited, intrigued and ready to dig in and do more research as one of the legion of Scippigræd who are attempting to follow the path he has masterfully forged for Tolkien scholarship. May his, and all those he has “counselled,” explorations continue!